Current Projects

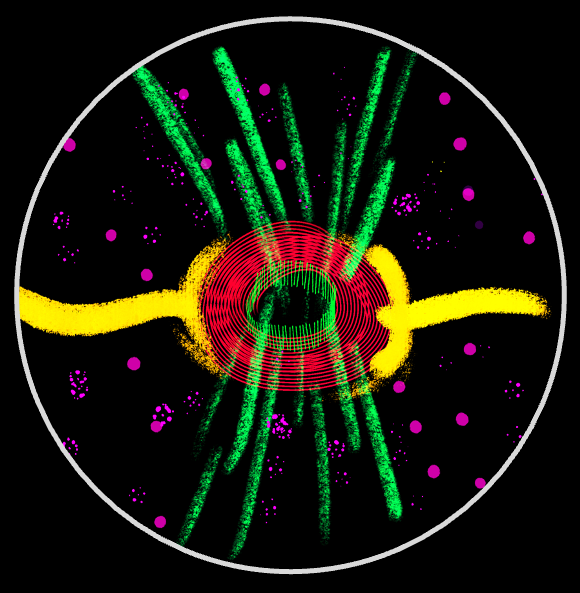

Cytoskeletal mechanics of germline bridges

Intercellular bridges (ICBs) are conserved ring-like structures that maintain cytoplasmic continuity between sister cells and are hallmark features of germline cysts—the precursors of oocytes and sperm—across the animal kingdom. In the Drosophila melanogaster 16-cell cyst, 15 ICBs link nurse cells to each other and to the oocyte, mediating directional cytoplasmic transport. ICB function relies on a robust cytoskeletal architecture that stabilizes them within the expanding membrane and facilitates transport as the cyst increases its volume nearly ~1,000×. Our work investigates how these bridges assemble, how their structure is maintained, and how they support oogenesis.

Forms and motility of non-canonical sperm

Sperm are among the most diverse cell types in nature, evolved to function—often—outside the body that produced them. Building on a rich literature of in vitro studies of sperm behavior, we aim to uncover how non-canonical sperm forms—such as the unusually large “giant” sperm of Drosophila and the corkscrew-shaped sperm of certain plants—are constructed and how they move, both individually and collectively, within their native environments.

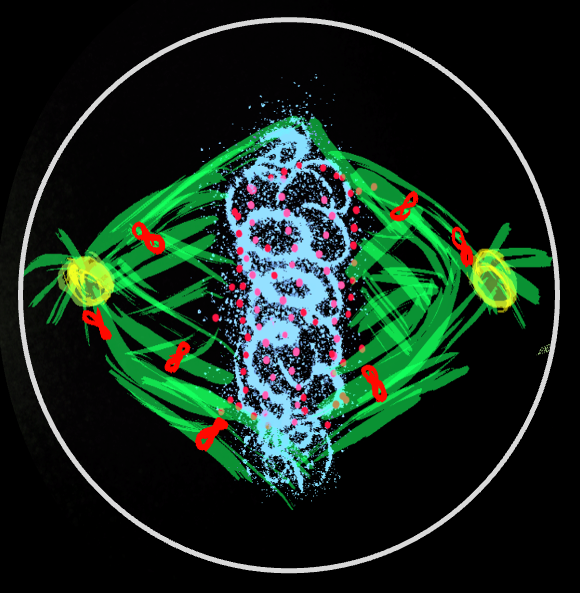

Positioning and dynamics of intracellular organelles

Intracellular organelles, including centrosomes, mitotic spindles, and nuclei, are actively positioned within cells, a process essential for establishing polarity and ensuring proper growth and division. Take the mitotic spindle as an example. Astral microtubules emanating from the spindle poles engage cortically anchored dynein motors, whose pulling forces position and orient the spindle. In our work, we combine live microscopy of C. elegans embryos with genetic and biophysical perturbations and mathematical modeling to investigate how these forces stably orient the spindle, set its elongation dynamics, and regulate its oscillations.

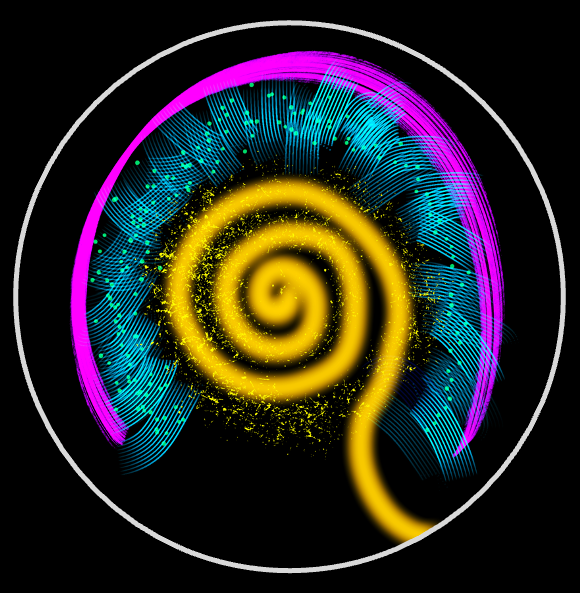

Self-organized cytoplasmic flows in large cells

Cytoplasmic streaming regulates diverse intracellular processes, particularly in large cells where diffusion and motor-based transport are too slow for efficient long-range mixing and cargo distribution. A prominent example is the cytoplasmic flows in the Drosophila oocyte, which arise during mid-oogenesis when kinesin-1 drives free microtubules and associated cargoes along a dense network of cortically anchored microtubules. We combine live imaging, quantitative flow measurements, and theoretical modeling to investigate how hydrodynamic interactions among motor-laden microtubules spontaneously generate and sustain these flows.

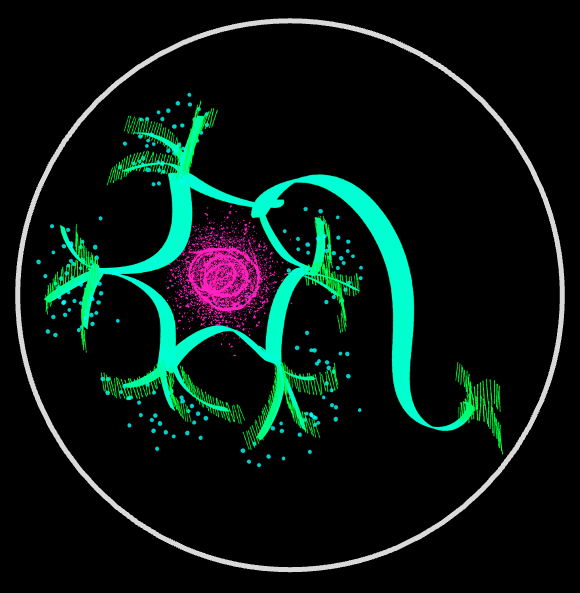

Growth and transport in primary neurons

Neurons grow and maintain processes that can span up to a meter in length. Yet the genes encoding the proteins required for this growth are transcribed in the nucleus, often far from distal growth cones at the tips of elongating axons and dendrites. This raises a fundamental question: how do neurons build and maintain such extreme morphologies, and how do they achieve selective, long-range transport of molecular and cargo along axons and dendrites? We combine long-term live-cell microscopy with quantitative analyses of cell morphology and cytoskeletal organization to develop a predictive framework for neuronal morphogenesis and cargo transport along axons and dendrites.